Let’s take a little time and talk about rhyme. So, if I were to take that first line and divide it into two end-stopped lines of poetry: Let’s take a little time/and talk about rhyme I’d have the classic end-stopped exact rhyme we were introduced to as children. Rhyme can be that simple—and that ho-hum. However, if used in a more complex way rhyme can heighten the musicality of your writing. There is a great deal one can say about rhyme.

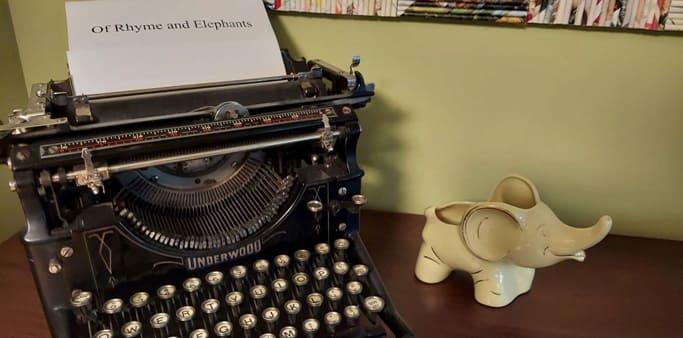

But first, we need to address the elephantine question that’s lurking in the room—must a poem rhyme to be considered a poem?

Dear Elephant: We love you. However, things change with time. Western poetry is no longer defined only as lines that must be end rhymed exactly. Most poems published today do not. We’re sorry. That’s just the way it is. The enjoyment of wide-ranging free verse put an end to that. However, this is not to say that rhyming has died out. Oh, no! It’s simply become more versatile—even a bit subversive. Let’s take a look at some rhyme variations and what we can do with them.

Alliterative rhymes (assonance and consonance): Alliteration is the repetition of sounds within words. Alliteration is most often defined as repeated initial sounds (head rhymes), but its subdivisions include assonance and consonance. Assonance: repeated vowel sounds. Consonance: repeated consonant sounds. Use of assonance and conso- nance can give your words rhythm. And when continued into the next line, it can link the lines in a lyrical way. Look at these examples:

Alliteration:

“…and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees…”

This is a line from Caged Bird by Maya Angelou. Why did she insert the word soft? The line would make perfect sense without it. It’s because it completes a musical phrase, soft through the sighing, that separates the two T words trade and trees. It also anchors the line by hugging those two internal T words through and the between two S words, soft and sighing. That’s four T sounds in one line (two TR sounds and two TH sounds). And counting the final S in winds and trees, we have four S sounds! It’s a master class on the technique in a single line. (And we could go on about her use of meter in this line—but meter is a whole other discussion!)

Assonance:

When I forget to weep

I hear the peeping tree toads creeping . . .

These lines are by Ruth Stone from a poem titled Mantra. Here the long double EE plays throughout the poem without any regularity and seldom at the ends of lines. This repetition helps the poem hang together and creates aural pleasure.

Consonance:

I didn’t as

what kinds of things

hide behind black trees . . .

These lines by Jane Yolen, from her Caldecott winning book in verse Owl Moon, repeat the hard stopped letter “K.” This is appropriate as it is a bit of a scary scene for a young child going owling with her father in the middle of the night. This kind of subtle use of consonance adds atmosphere. For even more atmosphere using various forms of alliteration, all you have to do is read some of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.

Internal rhymes: These are rhymes in the midst of a line rather than at the end. Such as these by Rowena Bennett in the poem The Witch of Willowby Wood. (Notice the alliteration.)

There once was a witch of Willowby Wood, and a weird wild witch was she,

with hair that was snarled and hands that were gnarled, and a kickety, rickety knee . . .

Many poetic forms actually require an internal rhyme or two. For example, the Vietnamese Lục Bát (Check out the article on Lục Bát in the Sept./Oct. 2021 OPAP.), or several of the Welsh or Cornish englynion.

Penultimate rhymes: Words that rhyme on the second to last syllable, such as roaster and toasting are called penultimate rhymes. Listen closely and you’ll find this in many song lyr- ics. This allows for a great deal of leeway as to that final syllable. If sung, or read aloud, the last syllable can be extended/chopped/enjambed (slid into the next line), and the rhyme will still jump out to the listener. Here’s an example rom Bob Dylan’s I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.

We’re gonna forget it.

That big, fat moon is gonna shine like a spoon,

But we’re gonna let it,

You won’t regret it.

In Robert Creeley’s The Conspiracy the penultimate end rhyme makes use of assonance.

Things tend to awaken

even through random communication.”

Dactylic rhymes: Dactylic rhymes are rhyming words that have a dactylic beat (hard-soft- soft). Such as terrible and wearable. Look below at the wonderful dactylic rhymes from Nonstop in the play Hamilton. (Note that the penultimate syllables rhyme exactly in two of the words, and pretty dang close in the third!)

Now for a strong central democracy

If not, then I’ll be Socrates

Throwing verbal rocks at these mediocrities…

Slight/slant/sprung rhymes: Slant rhymes are syllables/words that almost rhyme. Songs often bring two words that don’t rhyme closer to each other by the vocalization of the singer. These rhymes are handy for poets who can still solidify the piece but forego an exact rhyme—knowing that our ears will almost hear it as a rhyme. For example, the two slant rhymes girl and world in Prince’s song Kiss:

You don’t have to be rich to be my girl

You don’t have to be cool to rule my world.

Also, slant rhymes can be used where disruption, surprise, or an unsettled feeling is want- ed. (It’s that subversive ability of rhyme I mentioned earlier.) Here’s an example by W. B. Yeats rhyming young with song.

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees

– Those dying generations – at their song . . .

Subversive use of rhyme: Slant rhymes can be used to shake us up a bit. In addition, there are poetic forms that might throw an English speaker/reader for a loop. Some traditional forms require the first syllable of each line to rhyme, not the final syllable. Also, there is a form called the wrenched rhyme which is rhyming a stressed syllable with an unstressed one—such as, caring and wing. And I haven’t even mentioned sight/eye rhymes such as good and food. All these techniques, and more, that slightly jostle us off our feet can be used to produce surprise, humor, or disruption.

So, Dear Elephant: Although most American poetry today is not defined by exact end rhyme, it is still fun to jump in and play with other rhyming techniques. Wanna join me?

[NOTE: This article first appeared in Of Poets & Poetry, published by the Florida State Poets Association. Nov./Dec. 2022]

Some poetry/songwriting links to further your practice: https://www.izotope.com/en/learn/5-types-of-rhymes-you-can-use-in-your-song.html https://oxfordsongwriting.com/stephen-sondheim-on-songwriting-1/ https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-write-in-rhyme#10-different-rhyme-schemes And see Shutta’s handout “Poetry 101,” at https://shutta.com/resources/